Towards Criminal Intelligence: Data Prospecting or Selecting Significance?

This article was first published in 2006 in the IALEIA Journal Vol.17 No 1

I. A new policing strategy?

When asked to describe the nature of their profession, investigators, whether or not they acknowledge the role of analysis, are likely to refer to a reliance on their training, experience and common sense in discovering the truth. Anyone who has witnessed a court hearing would likely comment that the truth is often an individual construct which depends on one’ s point of view and that often the investigator’s truth appears differently in terms of evidence. Notwithstanding the skills and training of an investigator, criminal investigations are essentially about the logical management of information: making the best use of that which is available, using it to uncover further information and recreating from it as close an understanding of the truth as possible.

The vast volumes of data now available to the modern investigator or analyst, have generated a need for a methodology for marshalling information into manageable bites – not least because a failure to address any relevant fact or material discrepancy is a weakness exploitable by a defence team to establish reasonable doubt. It cannot be denied that things are sometimes overlooked because their significance is not obviously apparent. Recognising this significance is not always easy. On the strategic level too, crime managers are today confronted with substantial levels of unwanted, irrelevant or inappropriate information in increasingly variable formats. The trick is to separate the wheat from the chaff and intelligence-led policing is one response to the very real need to focus on those data which are of greatest value.

In support of the intelligence-led approach to policing, this document suggests a theoretical concept by which that information which is most critical for decision making may be systematically recognised and, in doing so, attempts to promote the common ground between investigator and analyst by exploring similarities in their respective needs in an information environment. In a time before the world became dominated by the microprocessor, M.A.P. Willmer considered the relationship between crime and information. Adopting terminology from telecommunications theory he described criminals as emitters of signals which police seek to detect against the background noise of general information.

The more clumsy or unprofessional the criminal, the stronger the signal emitted. The more adept the police strategy, the easier it is for the police to locate the criminal’s signal. In Willmer’ s view, the value of an item of information can be measured mathematically in terms of the extent to which it reduces uncertainty in the investigation (Willmer 1971:12). Reducing uncertainty to virtually nil establishes a fact beyond reasonable doubt (Willmer 1971:16).

Recently intelligence-led policing has acquired a new prominence both as a doctrine and as a strategy for law enforcement. In many ways the term has become a new incantation aimed at revitalising tired approaches in the battle against crime. As such it is often used indiscriminately without a demonstrable understanding of its advantages or implications or investment needs. In this document it is defined at its most succinct as the use of intelligence to inform the allocation of resources and tasking of effort. Such a definition implies the need for a coherent and universal intelligence model and this is now being increasingly recognised on the national and international level.

In 2000, the UK Government adopted the National Intelligence Model as part of its policing strategy (UK Home Office, 2005), four years later the European Union has included intelligence-led policing in its 5 year programme for freedom, security and justice (Council of the European Union, 2004, p22) and the USA established the National Criminal Intelligence Sharing Plan (US Department of Justice, 2004). Each of these initiatives recognise that the structured handling of information promises substantial advantages for law enforcement.

Mainstream thinking considers an intelligence model to have four principle components:

- targeted crime level or category;

- tasking;

- analysis; and,

- products.

Of these, analysis, normally focuses on the intelligence cycle as a framework for activity under the model.

For criminal intelligence analysts, the intelligence cycle of Collection, Evaluation, Collation, Analysis, Dissemination is familiar ground (although subject to some variation depending on the source). It is a clear expression of a general process that has the virtue of being applicable to many different scenarios. On the other hand, the intelligence cycle falls short of an adequate exploration of the relationship between data and investigatory needs or of the critical thought processes required to produce quality intelligence out of general information.

Whilst an analyst is dedicated to deriving meaning from data (Peterson, 1999:D) what we now need to develop is an efficient way of focusing on the data of greatest value without detriment to the derivation of meaning.

“Intelligence” as a term can have multiple meanings (particularly in the international context) and is unfortunately overshadowed by military connotations, but, for the purposes of law enforcement, it is defined here as information with significance or potential significance for a line of enquiry or investigation. The notion of significance is key and leads to a possible mapping a process by which significant data may be progressively identified.

II. Assigning Significance:

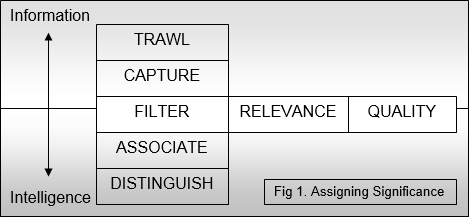

By reconsidering the first part of the intelligence cycle from the perspective of data selection, five steps can be discerned by which the significance of information is recognised and assigned through a cumulative process. These five steps can be termed: Trawl; Capture; Filter (with sub-categories of quality and relevance); Associate; and, Distinguish (fig.1).

Through this value chain information evolves into intelligence and becomes the starting point for analysis.

A. Trawl: Initial Selection

In intelligence-led policing, the gathering of information is directed and managed by reference to tasking and to a preset intelligence requirement. It implies more than a simple “collection” of information in that it involves a pre-selection of relevant data through targeted activity. If one considers the metaphor of a trawler, a trawler skipper alters the size and type of his or her net or selects a fishing ground in order to increase the likelihood of catching certain fish. This does not mean that other fish are not also caught up in the net, nor, indeed that any fish will be caught at all, but it does provide a predisposition which helps him or her focus effort in the area of greatest potential.

B. Capture

Once the data have been captured, they become susceptible to grading and the process of assigning significance may begin. It is at this point that data will be entered into some kind of filing system, either manual or electronic, so that they can be worked upon in an auditable environment which preserves their integrity and facilitates subsequent stages in the cycle.

C. Filter: Relevance and Quality

The filter stage begins the process of selecting or preferring certain information from the captured data pool through consideration of its relevance and quality. This may be achieved by a mixture of automatic and manual systems, but cannot be totally automated as the human element is indispensable for recognising the intrinsic value of data.

The level of relevance of captured data needs to be measured initially against whatever criteria have been set for the trawl or collection phase. In the intelligence-led approach this will be done by reference to an intelligence requirement on the strategic level or to the needs of an investigation on the tactical level.

Quality, from an intelligence management point of view, can be seen as consisting of a number of elements:

- Reliability (i.e. accuracy in terms of source and content);

- Intelligibility;

- Timeliness; and,

- Value (in terms of cost, opportunity and level of detail)

Under the heading of reliability, the degree of certainty provided by the data is of prime importance. It is in the nature of intelligence that ascribing certainty carries some measure of risk. One accepted way of mitigating that risk has been to consider the track record of a source and to assess the proximity of the source to the information (i.e. a source evaluation). There are a number of variations, but the 4×4 system which is widely used in Europe (Europol, 2003, p6) comprises the following coding:

(A) Where there is no doubt of the authenticity or reliability of the source;

(B) Where information from this source has been mostly to be reliable;

(C) A source from whom information has been mostly unreliable;

(X) Where the source is not previously known or cannot be assessed.

(1) For information which is considered accurate without any doubt;

(2) For information known personally to the source but not to the person providing it;

(3) For information not known personally to the source but can be corroborated by existing information;

(4) For information which is not known personally to the source and is not corroborated by other information or where the accuracy of the information cannot be assessed.

As can be seen, the letter code indicates the previous performance of the source supplying the data and the number code indicates how close that source is to having personal knowledge of the content or to being able to corroborate it. Thus a code of A1 is most reliable whilst X4 reliability is uncertain. Although the source evaluation code offers a way of assessing reliability, it is effectively a risk management process and, as a mainly subjective assessment, is clearly not infallible. As an evaluation, it does help to indicate where a piece of intelligence should sit on the continuum between fact and speculation, but it needs to be viewed critically and kept under constant review.

The remaining indicators of quality (intelligibility; timeliness; and, value) are interrelated, but are more an issue for managing the intelligence process than they are for relevance or for any particular analytical plan.

Intelligibility:

Unintelligible data brings with it two problems. The first is that it has to be returned to the sender for clarification and may, in the meantime, lose value. The second, greater, problem is the danger that the information may be read as having a different meaning to the one intended by its supplier. These are particular risks when dealing with multi-lingual data sources where a translation can miss the nuances or precision of “action on” wording and reflect similar problems to those highlighted by Willmer under the definition of “internally generated noise” where detecting criminal signals is made more difficult by ineffective police action (Willmer 1971:30).

Timeliness:

Timeliness of data is also important for a quality assessment, especially in the case of a live operation. Much information has a sell-by date and a lead-time before it can be processed and correlated. The late receipt or processing of data harms the integrity of the analysis and adversely affects decision making.

Value:

All data have value, both in monetary and analytical terms. In attributing value a subjective assessment is required in the form of certain questions: What level of detail do the data contain? Are they complete? Are they specific? Do they help to identify new lines of enquiry or close down wasteful ones?

Intelligence managers must also be aware of the various cost factors involved in collecting, processing and manipulating data:

1) There is a cost to inputting data into a database. They may cost more to input than they are worth;

2) Retrieving data has a cost. An inefficient filing system or a poorly structured data file will take longer and be less efficient in answering an enquiry;

3) Data also have a cost linked to their acquisition. Costs of signals intelligence (Sigint) or technical surveillance are linked to the cost of the science, the equipment and the systems maintenance. Information obtained from an informant carries the cost of any payout made and the costs of running that informant.

Costs in this context are, however, more an issue for intelligence managers (particularly those involved in the tasking and targeting process) than for any particular analyst or detective. The intrinsic value of data in an investigation does not rely on the cost of their input, retrieval or acquisition, but on an objective assessment of their relevance and, following Willmer, to what degree they reduce uncertainty.

D. Associate

Once relevance has been attributed to data, their level of significance can be further refined by considering the distinctiveness of the data in terms of their association with or distinction from other data. Data which are highly distinctive have more value for an investigation or analysis than those which are common place because they are able to focus attention in a particular direction. Such data can be said to be dissociated from the pool of common attributes, but associated with the investigation. Conversely, common place data which lack inherent distinction, can gain in significance when, through association with other pieces of common place data, a cumulative and distinctive relationship becomes apparent. For example, a report of “a man with freckles” by itself has little intrinsic value. The number of “men with freckles” in the general population means that, without more, the value of this one report lacks significance, but, should several crime reports mention “a man with freckles”, then that piece of information, allied with the other similar data, becomes highly significant.

E. Distinguish

It should also be borne in mind that items of information “can all be useful. They will not, however, all be as useful….There will be occasions as well when the same basic type of information will have different degrees of importance” (Willmer 1971:15). In relation to any investigation or analysis, the data of greatest significance will be those which are either unique (e.g. DNA, fingerprints, ballistics) or rare (e.g. missing fingers, unusual tattoos) because, as mentioned above, they allow a concentration of effort in a particular direction which would otherwise be unjustified. However, for Willmer, the detection process is “essentially one of finding information which increases the probability that some people are guilty whilst decreasing the probability associated with others.” Thus a further useful link in developing a chain of significance is the extent to which data is indicative of guilt. Information inferring guilt (culpatory) or which removes a person or fact from an enquiry (exculpatory) may be of equal importance and its the importance needs to be assessed in the light of all other information.

III. Two Categories of Significance

In this paper, intelligence has been defined as, “information with significance or potential significance for a line of enquiry or investigation”. Information which has been processed through a cumulative consideration of relevance, quality, association and distinctiveness, can be assigned significance with some confidence, but that significance can itself be further subdivided. Willmer drew a distinction between “active” and “passive” information. In his terms “active” information is that which leads directly to establishing a set of suspects (Willmer 1971:14) against which “passive” information can be assessed to see whether suspicion is either increased or decreased against that suspect set.

By reframing Willmer’s terms into a wider context, we can say that significant information falls into two categories. Where it is pertinent to a current enquiry, significance can be considered obvious or “active”. However, even where significance is not obvious, data may still retain a potential significance either because they are linked or associated with other data or because they open up a new line of enquiry. Where this applies, such information can be said to have “latent” significance.

In law enforcement, the objective is to bring criminals to justice or to disrupt their activities to such an extent that the harm is removed. In the former case, a court hearing is the endgame and it is evidence (i.e. the “active data”) which will determine the verdict, however, in most jurisdictions, evidence, will be either admissible or inadmissible. Admissible evidence is relevant information which can be heard before a court whilst inadmissible evidence is also relevant information, but which, because it may not be the best source of information available or because it may be tainted in some way, may not be heard in court. In an intelligence process the issue of admissibility is less important, but, for an investigator to achieve a conviction, it is paramount; All relevant evidence must be disclosed and any evidence which is exculpatory may supply the reasonable doubt necessary for an acquittal. On the other hand, whilst inadmissible evidence cannot be heard in court, it may nevertheless overwhelmingly suggest guilt and even generate intelligence which can be used to locate further admissible evidence. In establishing the significance of data, therefore, the level to which data are indicative of guilt must also be assessed. They allow an enquiry to focus on the perpetrator and serve to increase the weight of evidence in a trial.

IV. Critical Vectors

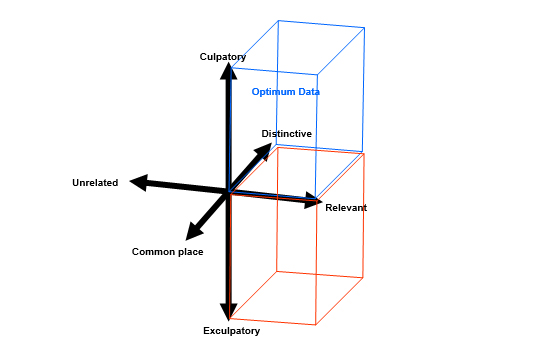

The above reasoning seeks to describe a logical progression which accompanies the transformation of raw data into intelligence as they are ascribed value and significance. The conceptual framework which results can be summarised in four vectors which provide a framework for assessing the significance of information:

a) Fact – Speculation;

b) Relevant – Unrelated;

c) Distinctive – Commonplace;

d) Culpatory – Exculpatory.

The primary vector, Fact – Speculation, has an overarching applicability and, since its value not only affects the other three, but is varied by them, it should be kept under constant review. However, with this in mind it is possible to plot the remaining vectors on a three dimensional model which can demonstrate the likely coordinates of optimum data in diagrammatic form (Fig 2).

As can be seen from the diagram, the optimum data set for any particular problem will consist only of those data which are (a) significant, (b) directly relevant to the matter at hand; (c) distinctive either through their uniqueness or through their association with other data; and (d), indicative of guilt or innocence. In terms of the most compelling case for court, the optimum data could be described as those admissible data which are most relevant, most culpatory and most distinctive.

Fig. 2 Critical Vectors of Significance

The intelligence cycle is a valuable tool for understanding the various stages of analysis, but it does not reflect the strong symbiosis between investigation and analysis in intelligence-led policing. The critical vectors of significance proposed above allow for the identification and application of an optimum data set amenable to both analysis and investigation and are offered here as a starting point for further debate and for future development in association with a common intelligence concept.

References:

Council of the European Union (2004) the Hague Programme: strengthening freedom, security and justice in the EU, 16054/04, Brussels

Dixon, A (2003) Intelligence Management Model for Europe: Phase One from Scottish Police College, http://www.tulliallan.police.uk

European Police Office (2003) Europol Intelligence Handling, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities

Home Office (2000) The National Intelligence Model – Providing a Model for Policing Retrieved 18 February 2005 from http://www.policereform.gov.uk/implementation/natintellmodel.html

Peterson, Marilyn B. (1999) The Basics of Intelligence Revisited, from CD ROM “Turn-Key Intelligence: Unlocking your agency’s intelligence capabilities Version 1.0” Published by IALEIA, NW3C and LEIU

US Department of Justice (2004) Press Release: Attorney General Ashcroft announce implementation of the National Criminal Intelligence Sharing Plan, Retrieved 18 February 2005 from http://www.usdoj.gov/opa/pr/2004/May/04_ag_328

Willmer, M.A.P. (1971) Crime and Information Theory, Edinburgh University Press